I’ve been reviewing comics about dysfunctional relationships this week (Lulu Anew, Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam and Other Stories), so I think it’s best to finish the week off with Robyn Chapman’s latest comic, recently published through a small Kickstarter project this winter. Chapman has slowly been plugging away as the publisher of the micropress Paper Rocket Comics, and I’ve known about that work for a while now, but Twin Bed is my first introduction to Chapman’s work as a cartoonist.

(Images of the book and interior pages were shamelessly taken from the book’s Kickstarter project because my scanner is still on the fritz)

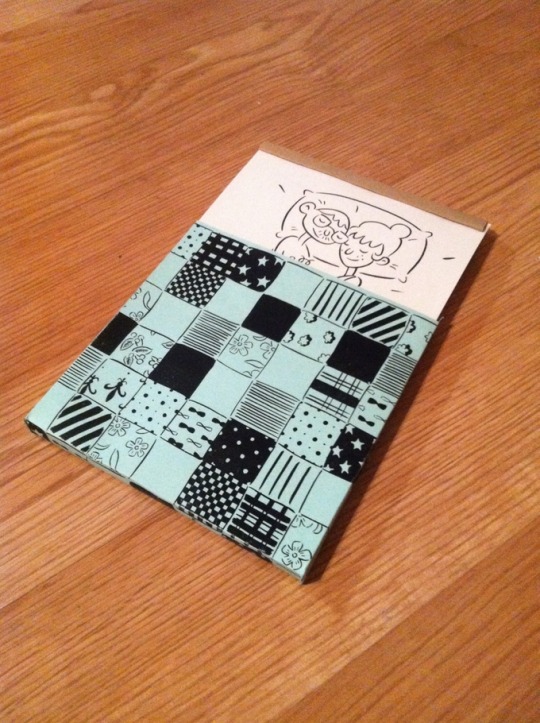

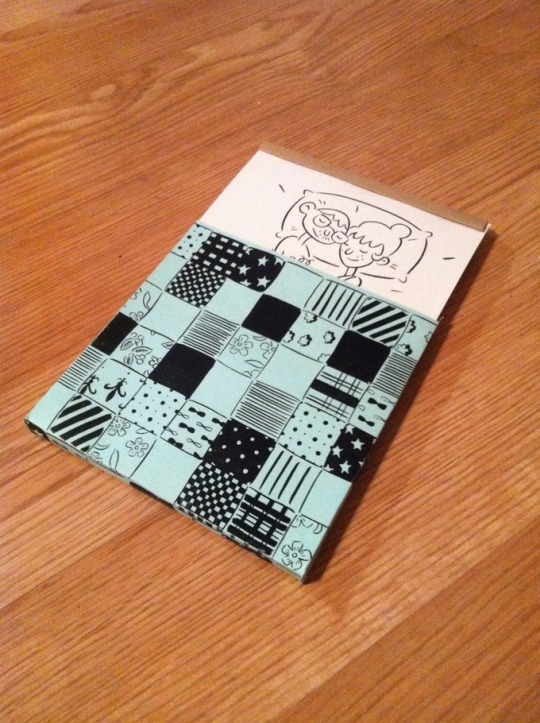

The construction of Twin Bed, a black and white 100 page graphic novella, is worth considering – the front cover, an image of the two main characters sleeping, is obscured by a slip case that is printed so as to look like a quilt. The book is bound like a steno pad, which gives it the look of a bed with a headboard – and if the book is the bed, then you as the reader are lifting off the covers to read the story. In a sense, the act of reading is transgressive; you are a set of a prying eyes in an intimate place.

The work carries this theme of prying eyes through; the reader sits at a fixed point in a tiny room barely big enough for a twin bed. From that vantage, we see an interaction between two unnamed characters in that space, watching TV, having sex,, sleeping, arguing, and getting into fights. The book progresses as a series of dates, each of which happens in a series of a few pages. As the relationship becomes more and more strained, the man in the relationship becomes verbally abusive and manipulative.

The page design, up until the very end, is the image of the man’s room, which Chapman captures using a base image that is static with characters and speech bubbles rendered over it. The result is a space in a state of constant sameness, and the narrative mirrors that in some ways with a relationship that ebbs and flows, and then finally runs dry.

There is a negative aspect to being focused on one living space throughout the entire book. Because we only see the male character’s knick-knacks, Star Trek posters, and long boxes, there’s a hyperfocus on not just the bed and the room, but the guy that lives in the room. I felt that I understood the man as a character better than the woman because of the structure of the comic.

This is not to say that every narrative needs to show all sides of a story. I think that in staying in a fixed place, Chapman creates a much more cohesive work. Chapman’s characters are cartoony and decidedly average, and the art is crisp, if workmanlike.

There’s a simplicity to Twin Bed that is appealing. The place where Twin Bed excels is in the integration of smart formal elements that make sense for the narrative Chapman is trying to tell. This is a smart book, and worth a read.