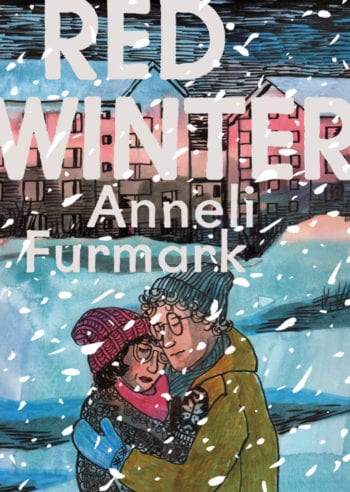

Some books demand to be reviewed. This is certainly the case with Anneli Furmark’s period drama Red Winter, set in 1970s Sweden, where a secret affair between a young man named Ulrik and an older woman named Siv ricochets around a small northern community. Red Winter is Furmark’s first comic to be published in English, and Hanna Stromberg’s translation from Drawn and Quarterly is an essential establishing point for what will hopefully lead to more translations in the future.

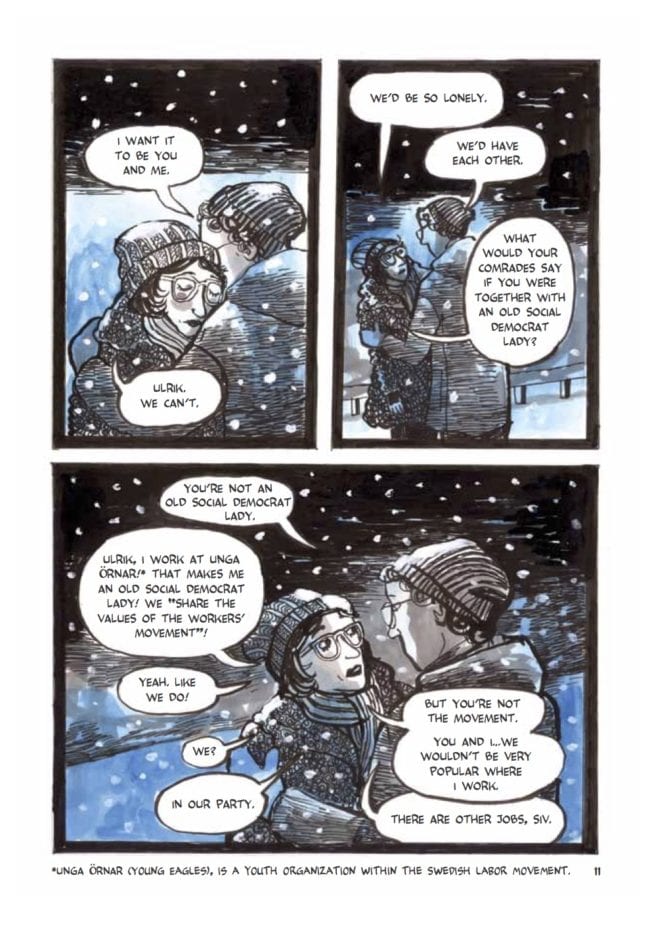

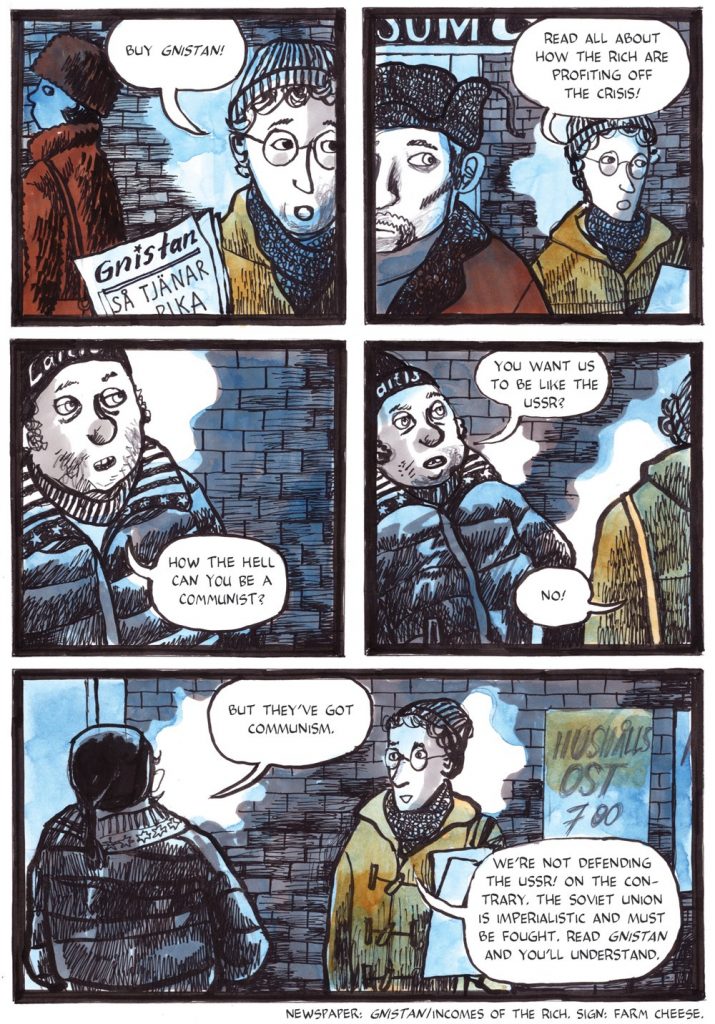

As Red Winter opens, we see a pair of lovers huddled together against the winter cold. Siv and Ulrik are the pair in question, and they’re an odd pair. Siv is married and has teenage children, and Ulrik is 10 years her junior. More important to the drama of Red Winter is the political climate. The two share different political ideologies; Ulrik is a part of the Maoist SKP party and Siv is a member of the Socialist Democrats. This isn’t really like a current-day Democrat dating someone in the Democratic Socialists of America; during the 1970s, Sweden entered a period of strife as the Socialist Democrats were thrust from the seat of power and leftist groups attempted to wrest control of the government to overthrow capitalism. During this time, the SKP was trying to militarize and gain control of various unions and was openly hostile to other political parties.

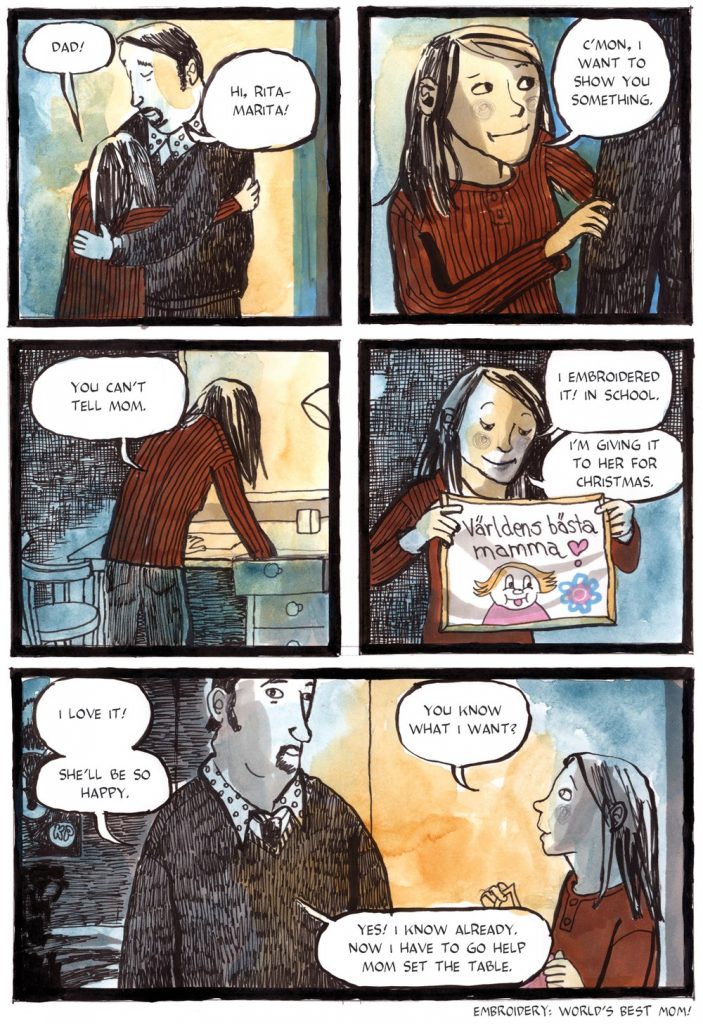

The heart of Red Winter is the subterfuge that exists in each of the characters’ plot lines. In the main love story, Siv fears discovery because of the effect it might have on her family, while Ulrik fears discovery because of the zealotry of his comrades in the SKP. Meanwhile, Siv’s daughter, Marita, sneaks money out of the house and reads her mother’s diary while her son Peter gets into trouble with friends at late hours. There’s a sense, even early on, that discovery of these things is inevitable. Early in the book Siv meets up with Ulrik in the middle of the night and sees her son speed by in a friend’s car. Marita is reading Siv’s diary. Ulrik’s comrades are paying attention to his lackluster performance at meetings and selling the SKP newspaper. They’re also paying attention to his late night trysts. It’s a combination that is bound for disaster.

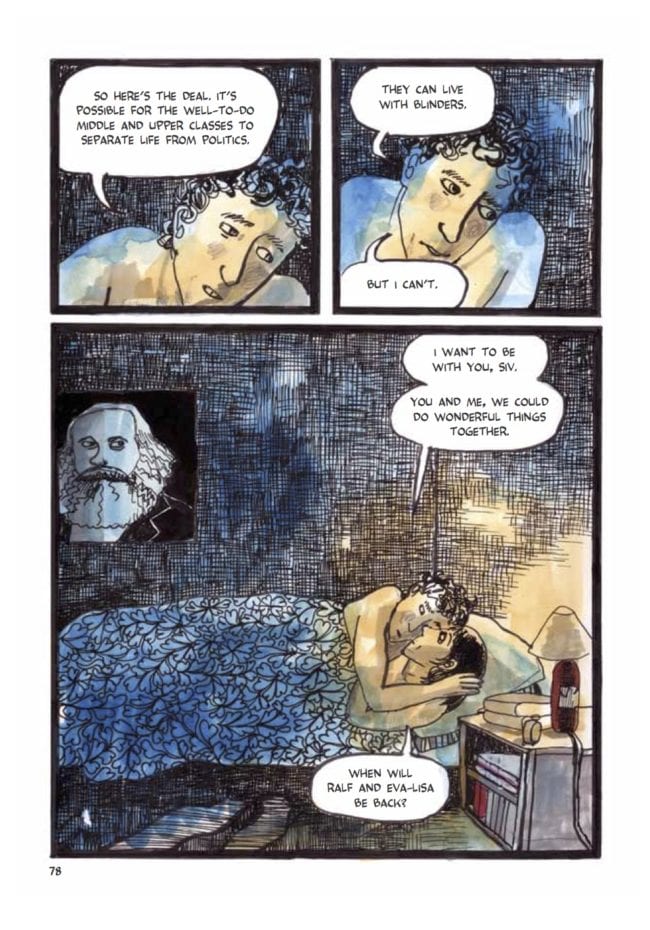

Furmark’s illustration, with its predominant dark greys and blues, mirrors the snowy, frigid landscape of Sweden in winter. But reds and oranges sneak into the intimate moments of Red Winter; these colors are lamps in the darkness of the winter bleakness, a light by which these people move through the paths of their lives. The color work is primarily done in what looks to be watercolor or gouache, and Furmark layers inks over that canvas, and all of it is remarkable. There’s a sense of dreariness to these colors, a sense that it is not just the weather oppressing the people of this small Swedish town. And there’s a poetry to these colors, much like there is a poetry to Siv’s meandering thoughts on love and life.

In a story where everyone is hiding something, what is seen and unseen plays a distinct and important role in that work, and Furmark does an excellent job of emphasizing that in Red Winter. What characters know and don’t know is essential to the push and pull of the plot. But more importantly, Furmark plays with the idea of what is seen and unseen by the reader themselves, and this feature of the comic elevates its storytelling. Nowhere is that more true than in the actual end of Siv and Ulrik’s relationship. When Ulrik’s relationship with Siv is revealed by his communist comrades, he ends up being sent even further north to assist another commune. Siv bares all to her husband and news gets around to everyone in town. We see all of this on the page; we see them disgraced and belittled. But the actual end of their relationship happens off-page, unseen by the reader. Marita gives readers a final sense of the outcome of in Siv’s family, where the fate of Ulrik is essentially unknown. Left to the reader’s imagination, this outcome is possibly even more heartbreaking.

Red Winter isn’t a thriller and it’s not especially daring or risque. The love affair of these two people in difficult political times is a story of normal people living common lives. But Furmark’s strong pacing, beautiful colors, and poetic language give Red Winter an uncommon charm. I found myself transfixed by the power and the subtle beauty of this comic.

Sequential State is made possible in part by user subscriptions; you subscribe to the site on Patreon for as little as a dollar a month, and in return, you get additional content; it’s that simple. Your support helps pay cartoonists for illustration work, and helps keep Sequential State independent and ad-free. And if you’re not into monthly subscriptions, you can also now donate to the site on Ko-Fi.com. Thanks!