There’s a whole story to write about the publication of Hobo Mom, a recent release from Fantagraphics. Charles Forsman and Max de Radiguès are recently published authors from the press, and Forsman specifically has had some recent popular success with the adaptation of his comic The End of the Fucking World for a Netflix series. This is kind of a watershed moment for Forsman, a cartoonist whose work in the past has been critically lauded but sort of flew under the radar, and makes his current and previous work highly marketable.

The publication of Hobo Mom is timely for new fans of the pair of cartoonists (or for anyone who liked the TV show and wanted to check out Forsman’s other work), but the comic started as a collaboration between Forsman and de Radiguès all the way back in 2014 with Italian publisher Delebile. Forsman and de Radiguès are no strangers to collaborating; Forsman’s small press Oily Comics published zines of some of de Radiguès’ work, including Bastard, his recent book from Fantagraphics. Plenty of cartoonists collaborate on comics, but Hobo Mom is a special case, because it attempts to seamlessly blend and centralize on the similarities between the two cartoonists’ illustrative and writing styles.

Hobo Mom was originally printed in Italian (with English translation sheet included), and the book had a limited distribution in English-reading countries. Effectively, the only way to get it was to buy the book online and spend a mint on shipping, or get it at one or two convention appearances by the Italian press. Now the novella-length comic has received a deluxe hardcover treatment with perfect binding from Fantagraphics. If memory serves, I originally read the Italian version a few years ago after getting a copy at TCAF. I recently revisited the comic with its new printing.

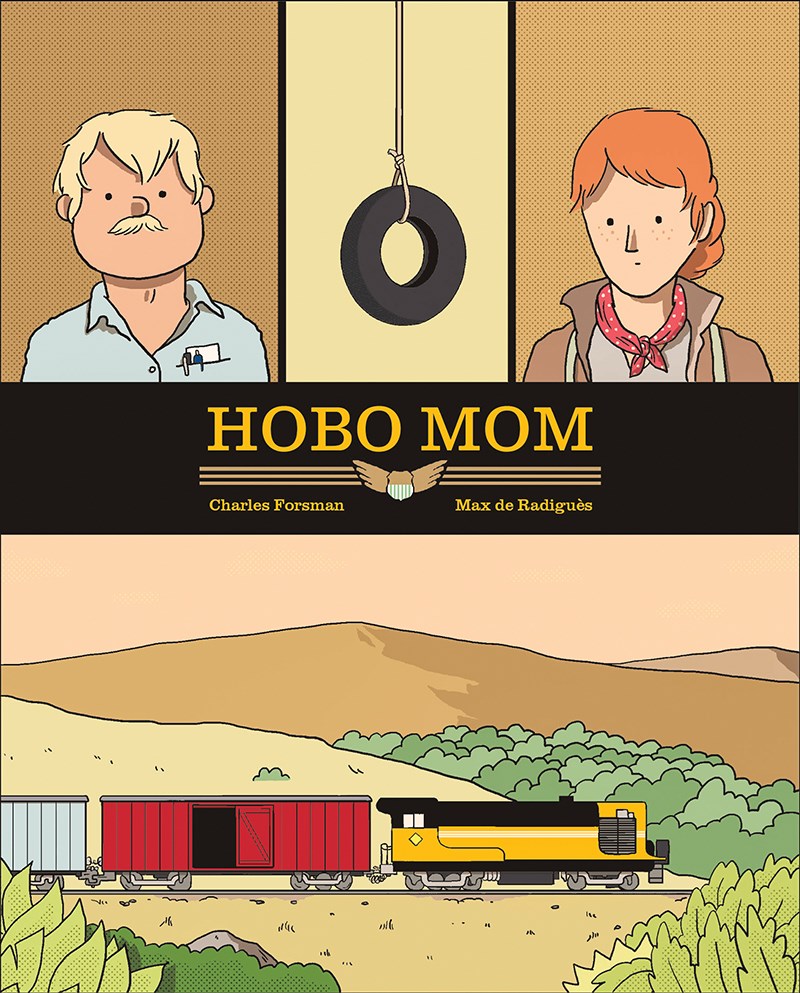

Hobo Mom is the story of three entwined people; Tom, a heartbroken locksmith, Natasha, a vagabond and traveller, and Sissy, their preteen daughter. Natasha is prone to wanderlust and has been living away from her family, but wants to find out more about her daughter, much to Tom’s chagrin. Sissy is initially awed by her mother, a female figure in her life where none was previously, but Tom is reserved, icy from the end of their previous relationship. But as Natasha stays with Tom and Sissy, that ice thaws, and complications ensue.

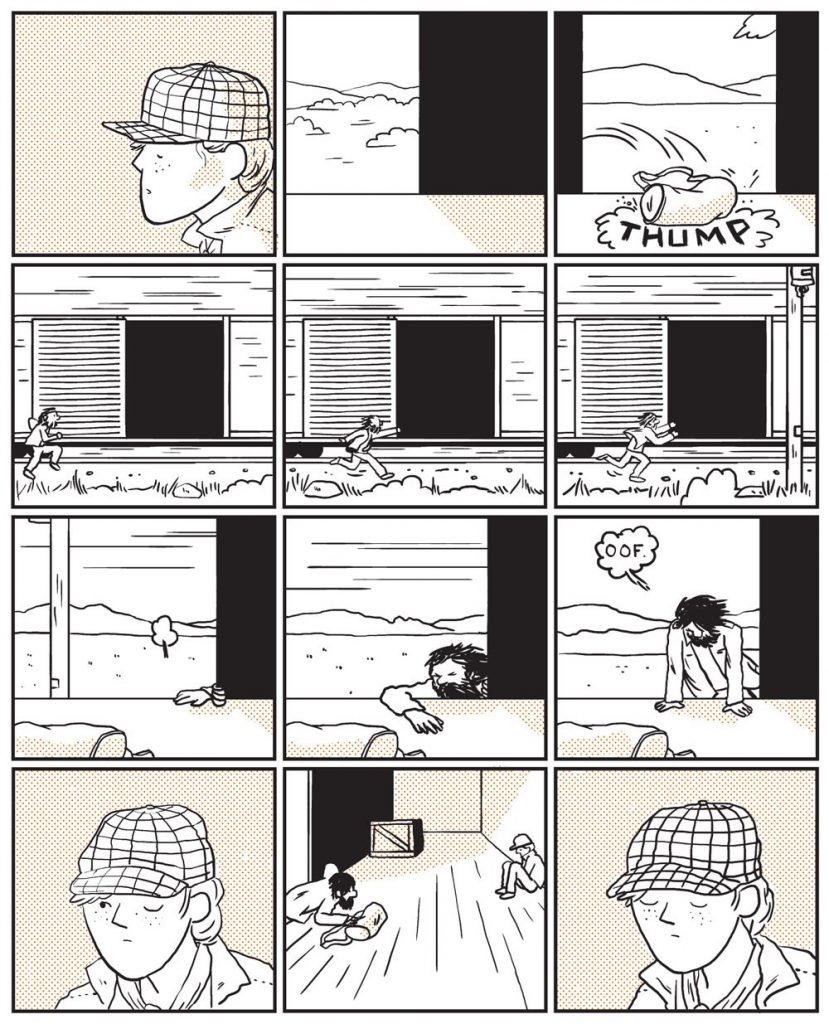

Forsman and de Radigués both have a simple, cartoony style that complements the work well. It’s interesting to see where their styles converge, and the result is competent, if not spectacular. Hobo Mom is already 4-5 years old at this point, and there were some drawings that had me scratching my head. It’s clear that both Forsman and de Radiguès have progressed as cartoonists in the intervening years; both Bastard by de Radigués and I Am Not Okay With This by Forsman are remarkably more assured works. I also love the coloring, which is sparse, and used mostly for effect. Forsman and de Radigués use a black and white page with a dusty pink Ben Day dot to bring depth to scenes, and I felt that this effect was a good fit for the comic.

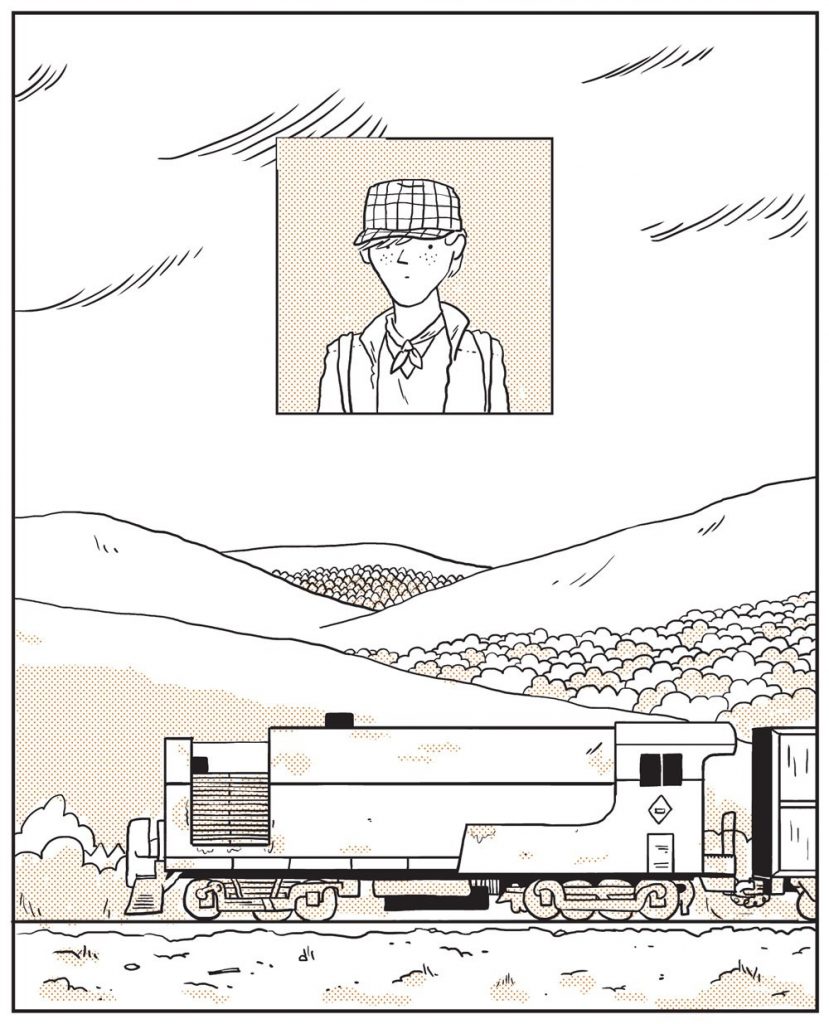

Hobo Mom is imbued with a subtle nostalgia, visible almost immediately in the title of the book and characterisation of Natasha. The concept of the hobo – a migrant worker who boarded running trains to move from place to place – is one that is nonexistent in the United States at this point. But the concept of the voluntarily migrant person allows Forsman and de Radigués to ask a simple question; what happens to a person who loves their family but can’t stay with them?

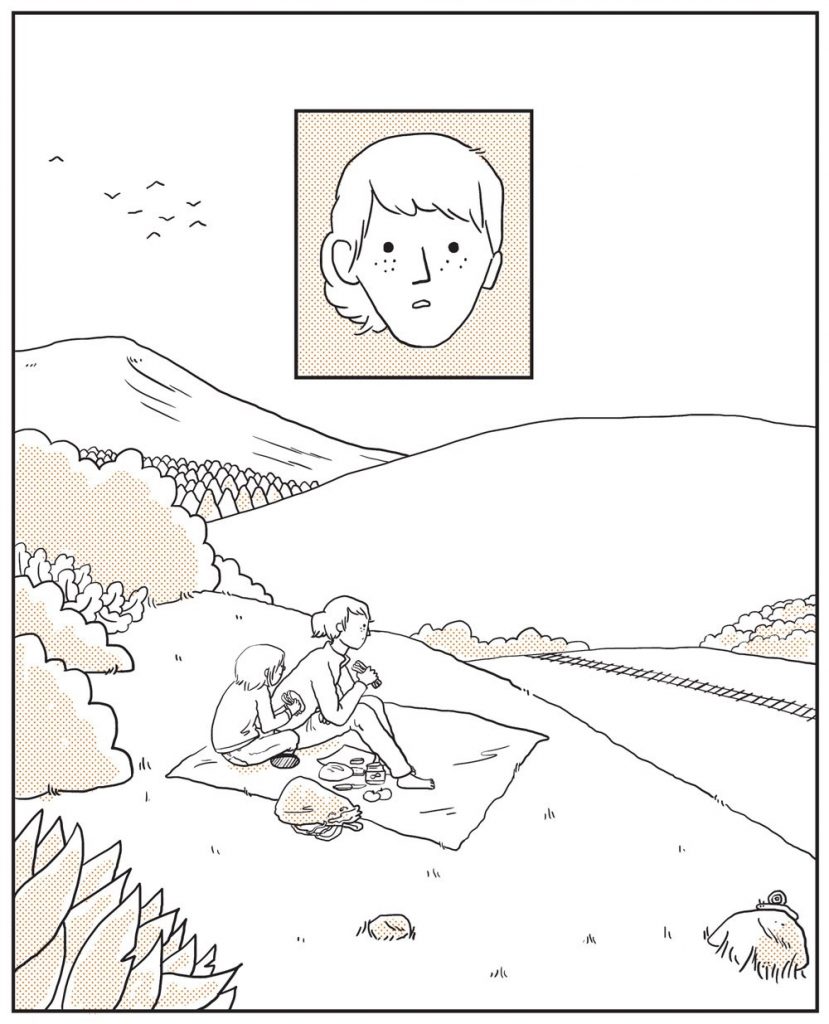

Like much of Forsman and de Radiguès other work, the storytelling of Hobo Mom is quiet and deliberate, but in my return to the book, I found it loaded with symbolism I hadn’t noticed before. Sissy’s pet rabbit provides the most in-your-face analogue to Natasha’s fate; the family home, with its dishes and its laundry, is just like the cage the rabbit lives in. While Sissy loves and wants to be loved by her pet rabbit, the only way they can be together is if the rabbit stays in the cage. There’s a sense of Natasha rebelling not against the concept of the nuclear family but against being tied down and held against her will, a rabbit in a different kind of cage. Natasha’s decision to leave her family in the first place was a decision between the cage and herself. This decision clearly haunts Natasha – she wants to be in her daughter’s life, in her lover’s life. But that decision to put herself in the cage comes at enormous cost.

There’s a formal inventiveness in Hobo Mom that mirrors this concept of the person in the cage; Natasha’s position inside of a panel within a panel mirrors the state she is in either literally or mentally. Other objects, places, or people also reside in that box; they are the cages the characters either enter by choice, or try to escape. It’s a small, but subtle effect that brings more resonance to the page.

Natasha’s re-entry into the family home has its consequences for Tom; it’s clear that he is nursing a broken heart and that her return is like ripping the packing out of a still-open wound. His emotions ride high when he encounters “regular families,” even when those families are broken in a way different than his own. His feelings of inadequacy and lack of control have him lashing out at Natasha when she returns. Those feelings color his behavior throughout the comic. But when the promise of his old life is dangled before him, as Natasha settles into the home trying to make things work, he can’t help but try to make for himself the normal life he wants, regardless of the consequences.

Both Forsman and de Radiguès are astute, emotionally observant writers; neither passes judgement on Tom or Natasha, where a lesser writer or collaborative would. Working relationships require sacrifice, that’s true, but there’s nothing working in theirs, and no amount of self-inflicted injury is going to make that right. Tom’s search for normalcy is ultimately the source of Natasha’s hurt, and it’s clear that there can be no ending where both are happy, whole, and together. I found Hobo Mom to be a quiet but powerful story, and I’m glad for the chance to revisit the comic in a beautiful hardcover.

Sequential State is made possible in part by user subscriptions; you subscribe to the site on Patreon for as little as a dollar a month, and in return, you get additional content; it’s that simple. Your support helps pay cartoonists for illustration work, and helps keep Sequential State independent and ad-free. And if you’re not into monthly subscriptions, you can also now donate to the site on Ko-Fi.com. Thanks!