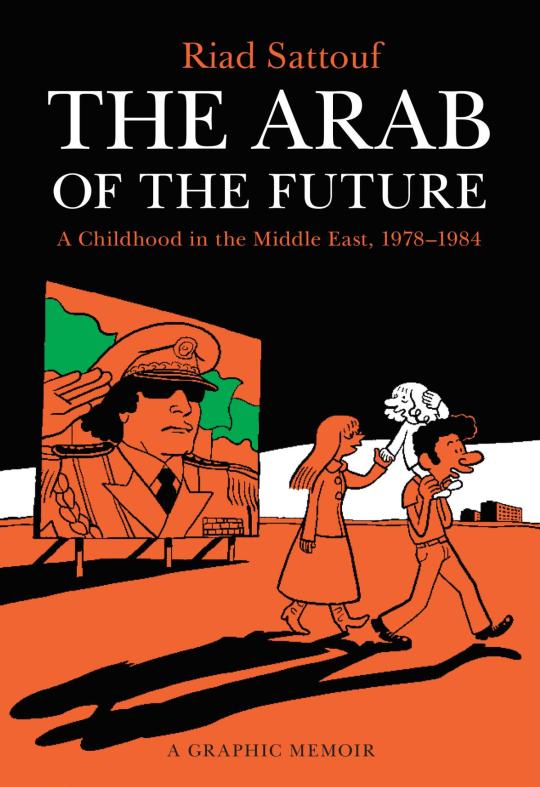

In October 2015, Macmillan released The Arab of the Future by Riad Sattouf. Translated from French, the book was a #1 French best-seller and is the first of what will eventually be a three part trilogy of memoirs by the French cartoonist. The Arab of the Future is a book that centers on a young Sattouf, his French mother, and his Syrian father as they travel for his father’s job as a professor. The family lives under the rule of famous dictators Gaddaffi in Libya, Al-Assad in Syria, and as the book jacket professes, a third dictator: Sattouf’s father, Abdel-Razak Sattouf.

CM is a cartoonist and comics critic living in Ann Arbor. CM’s critical work has appeared in various publications including the Hooded Utilitarian, where the piece “In the Wake of Charlie Hebdo, Free Speech Does Not Mean Freedom From Criticism” received a level of wider internet notoriety not generally seen by comics critics.

After an interesting but short series of messages on Twitter about the book, CM and I agreed to have a longer conversation to discuss The Arab of the Future and its successes and failings. It’s my hope that I can bring other cartoonists and critics to Sequential State to have more of these discussions, because I think that they’re a vital and very often underutilized way to critically evaluate work in the comics arena.

Alex Hoffman: Thanks CM for agreeing to talk with me about The Arab of the Future. I wanted to set up the conversation by starting with my gut reaction to the book, and then I think we can kind of proceed from there.

My first thought, after completing the book, was essentially bewilderment. I wasn’t really certain what I had read. The book, as described by its publication press and its book jacket blurb, explains how the reader will see Sattouf’s life under “three dictators,” one of which is Sattouf’s own father. But what I found was a fragmented and strange story about a very young child and his relationship with his family and his self-absorbed, racist father.

CM: Hey Alex, I’m excited to talk about this book! I’d heard a lot of good things about it, and when I went home over Christmas break my parents had checked it out from the library. I was honestly very taken aback as I read it – I hardly knew anything about the book going in, and I’d completely forgotten that Riad Sattouf was a high profile Charlie Hebdo contributor. The more I read, though, the less surprising that fact became.

The Arab of the Future

is an immensely popular book in France, so much so that Sattouf won the Angouleme grand prix for the first volume in 2014. I got very upset reading it, because it so thoroughly reinforces some very xenophobic and racist ideas that Westerners (especially French people) have about Arabs, and their relationship to the West. The book sets up a dichotomy very early on between French people and “Arabs” as a conceptual whole – Sattouf’s mother is French, and she’s portrayed as very sympathetic, decent, and normal. Sattouf’s father, on the other hand, is greedy, stupid, impotent, and bigoted. Now, I’m a big believer in harsh autobio, so Sattouf’s decision to emphasize those features in his own father didn’t really bother me, but the dichotomy that he set up between his parents is only emphasized as more characters are introduced. French people are, at worst, weird or lustful (Sattouf’s lecherous grandfather is given some emphasis) but their faults are miniscule and charming when contrasted with the almost uniformly savage and inexplicably cruel Arabs who appear throughout the book. I had to stop reading several times, actually, because I kept getting upset! Especially thinking about the refugee crisis happening in France right now, this books enormous popularity rung very sinister to me, because if you were to judge the crisis through the lens of this book, no Arabs should ever be allowed in – after all, their culture is one of cruelty, violence, oppression, and greed.

I understand, of course, that it’s difficult to tell a story as an adult about traumatic childhood memories. After all, kids weight different or foreign experiences differently than adults might, and they’re not privy to a lot of context that an adult might have. I didn’t see any consideration of that fact in Arab of the Future, though. Right from the beginning, Sattouf establishes that he was a beautiful, white-passing, blonde boy, and that almost every Arab person he met, young or old, treated him in increasingly inexplicably evil ways because of his appearance. He portrays these lurid, Orientalist fever dreams (for example, he goes to eat with his mother, who joins a group of Arab women in a room separate from the men. They disgustingly eat the leftovers of the meal that the men didn’t finish, and then they goad their children into savagely beating each other, almost ritualistically. There’s a lot of anti-Semitism too). I’m sure Sattouf isn’t lying about his own experiences, but the way that he sets up French society as stable, recognizable, and weird at worst as a diametric opposite of this hellish, nondescript, Arab nightmare-land says a lot.

There’s a very clear rhetoric to this book. The New York Times review very politely observed that the book “will do little to complicate most people’s perceptions of Libya or Syria. Life in both countries seems like a living hell, with no moments of relief or pleasure.” I would go further, and say that the book actively reinforces some very harmful racist stereotypes about Arab people, and at the same time valorizes the West as much more civilized.

AH: I think those are some very astute points, especially regarding The Arab of the Future’s rhetoric. One thing we know immediately about Abdel-Razak is his intelligence. He goes to study abroad to study in France, learns French, and defends a history doctorate while being fluent in at least 2-3 other languages. He is offered posts at prestigious universities, and he turns them down! But the way that Sattouf presents his father is almost as a comical opposite. He implies his father is a fool for turning down a Western university and taking a posting in Libya, positions Abdel-Razak’s long-term goal of building a palatial family home on his Syrian land as a pipe dream. Sattouf’s emphasis of his father’s personal racism, sexism, and xenophobia become almost hyperbolic in their presentation. Systematically we come to understand Sattouf’s contempt for his father by the way that he presents not just Abdel-Razak’s personal failings, but his greatest hopes.

To go back to your point about the way Riad Sattouf looks as a small child – I think the way Sattouf frames the very beginning of this book is very telling. He frames his 2 year-old self as “perfect” and describes his platinum blonde hair, his “refined and delicate” features, his “bright puppy-dog eyes.” This strange opening foreshadows the staging of the West vs. the Arab world in a really disturbing way. There’s a strange push and pull to Abdel-Razak, who in the beginning both loves France and Clémentine, Riad’s French mother, and then we see him slowly start to make more and more derogatory claims against the French and their way of life. When Riad, as a small boy, says that his cousins are calling him and his mother Jewish as an insult, Abdel-Razak belittles his son’s complaint.

I wanted to see what your thoughts were on the way that Sattouf draws the characters of his books; his cartooning is pretty precise, but I noticed that the character designs are emotionally drawn, in the sense that characters Riad had a bad experience with are drawn “ugly” while characters that are friendly are more likely to be drawn “cute.” I’m also interested in your thoughts on the geocentric color schemes that Sattouf chooses for his chapters.

CM: I’m glad you mentioned the ‘ugly’ characters, because that was something that really stood out to me. Especially the way that Sattouf chooses to draw the Arab bullies – kids around his age, or a little older than him. In contrast to the French kids, who are drawn as goofy or silly, the Arab boys are drawn in these really brutish, nasty ways. The implication being that they were born evil – they have evil features and they act cruel – it’s just a fundamental trait of theirs. Especially in the scene where a group of boys skewers an innocent puppy, Sattouf is very explicitly implying that these boys are just naturally bad, and that their shocking behavior is commonplace in the uncivilized and unjust society they are a part of.

The sensibilities that Sattouf is displaying, for showing shocking acts of violence or disgust (like when, swept along by a seemingly unstoppable narrative, he urges his little brother to eat a cockroach nest) isn’t uncommon in edgy comics that purport to show the Arab world “as it is.” I’m reminded of another French comics artist, Émile Bravo, and his comic from MOME 6 called Ben Qutuz Brothers in Frustration Land! (aka, the comic that caused me to recycle MOME 6 without any regret). Bravo’s comic is, on the surface, about the seemingly impossible to negotiate stalemate that occurs when strong, brutal ideologies clash with one another. In reality, though, it’s this racist piece of shit comic about evil Muslim Arabs! In the comic, the titular two brothers are living in occupied Palestinian territory, and harassed by Israeli soldiers. One Israeli soldier, a beautiful redheaded woman, shows some kindness to them when they’re unjustly detained. The younger of the two brothers is urged by his insane, fundamentalist parents, to become a suicide bomber. He blows himself up, ironically killing the beautiful Israeli redhead who had been kind to him earlier (in an unspeakably gratuitous, gory set of drawings that linger on her mutilated, severed head). The story ends with the older brother being sexually abused by an Imam, and the final panel shows the Imam’s bedroom door closing, emblazoned with a sign that reads “NO WAY OUT.” Do you get it, maaaaaannnnnnnnnnnn?????

This kind of story, that purports to show a stalemate or “both sides” of an issue involving Arabs and then portrays them in an entirely racist way, is typical of a Western, colonial mindset. The story is as Orientalist as any Fu Manchu book, with all the same trappings of being an honest account of the twisted ways of the East. In the end though, stories like Bravo’s amount to concern trolling at best, a highly exploitative and protracted “I just feel bad for those poor kids – they didn’t get to choose their parents.”

Anyway, that was a tangent, but man, fuck stories like this. As far as the geocentric color schemes go, I think that they further the kind of “Arab wasteland” narrative that the rest of the book sets up. France is nice, and kind of friendly (or, at least drawn in a much less oppressive way). Syria and Libya are both drab, utilitarian, boring, ugly, homogenous, cave-like places, full of danger and remorseless bullies. Tiny areas of beauty, such as Abdel-Razak’s beloved tree, are set up in contrast to the rest of the landscape.

AH: I thought the geocentric colors were an interesting creative choice, but I also had this feeling that they were more emblematic of Abdel-Razak’s overall mental state. France is a light blue and you notice that throughout he is feeling self-conscious and conflicted, and maybe slightly depressed. But he becomes more aggressive when he is in Syria, where the color is a light red/pink. I feel like the colors maybe don’t always work on that axis; there certainly is a potential connection just between the warm colors representing African and Middle Eastern and cool colors representing countries with cooler climates. Either way, I have no doubt in my mind that the each color choice is a deliberate decision.

I get what you are saying in terms of comparing Ben Qutuz Brothers in Frustration Land! to The Arab of the Future, but I think the former is a lot more vicious than The Arab of the Future is. I think that the mulberry tree that you mentioned is a good case in point, actually, and when the family eats together in the house they’ve been given after Abdel-Razak finds out some of the land he was bequeathed as a boy was sold by his brother. Do you think there’s any nuance to Sattouf’s portrayal of Libya or Syria? And how do you think the Sattouf family dynamics play into the overall narrative? Do you think that those family issues play into the larger narrative of “the cruel Arab” or are they more tangential?

CM: I definitely don’t want to go so far as to say that the book is without any nuance or serious thought on the part of the author. The cartooning has clearly connected with a lot of people, and the storytelling itself is very clean, and easy to read. You’re never brought out of the story by a clumsy drawing or weird transition – technically, these are very proficient comics, made by someone who has been a creator for a long time. So whatever ideological problems I have with the story, I don’t want to go so far as to say, “this is bad in every way,” or anything like that.

I agree that Ben Qutuz is more flagrant, but I mentioned it because it deals in some similar rhetoric, and the critical writing I’ve seen about it has largely mirrored the writing about Arab of the Future, in that it’s glowing, and while it might call the story “hard to read,” doesn’t find fault with the characterizations, since they’re portrayed in this kind of Vice Magazine “too gritty, too real” way.

It gets tricky for me to ask whether there’s nuance in Sattouf’s depiction of his own family, because, as I mentioned earlier, I think there’s a lot of leeway when it comes to depicting people who have had a big influence on your life, and who are related to you. I think of Bechdel or Gloeckner; I think either of them would say that their characterizations of family members aren’t 100% perfectly factual, but molded and simplified to work within the confines of the story they’re telling. That being said, I do feel that Sattouf’s family are fitting into the same larger rhetorical framework that’s present in the rest of the book: his Arab relatives are duplicitous, anti-Semitic, greedy, cowardly, and dumb, and his French relatives are, at worst, lustful or nagging.

The Nation ran a good article on this subject a few days ago, and it quoted a New Yorker profile of Sattouf in which he asked, “If I had written a book about a village in southern Italy or Norway, would I be asked about my vision of the European world?” That’s so dishonest! He’s a good writer, and it would be silly to think that he didn’t know exactly what he’s doing with this book, and exactly why it’s a huge bestseller in France right now. It just feels like Sattouf was Charlie Hebdo’s and is now France as a whole’s Arab friend. Like, “oh, it’s ok to say this stuff, because my Arab freind Riad Sattouf said it himself!” That’s how he’s situating himself, and he knows it. He could have written this memoir about his weird and difficult childhood experiences, his quirky family, and not framed it as Arab barbarism vs. French civilization. Instead, he titled the book, The Arab of the Future. I don’t know what his deal is, personally, but he definitely seems like more of a Marco Rubio than a Ta-Nehisi Coates.

In fact! The New Yorker profile says,

[Sattouf] claims to have forgotten the Arabic he learned in Syria, has no Arab friends, doesn’t follow the news from the Middle East, and knows no one in the Paris-based Syrian opposition. He told me that the first and only time he’d set foot in the Arab world since he left Syria was a weekend in Marrakech a few years ago. “It left me uneasy,” he said. “I had the feeling people were suffering from a lack of freedom, while Europeans were in bars eating tartare de dorade.”

I mean, how much more blatant can you be? He’s writing a book about, capital-A About the Arab world, and at the same time, he’s your cool Arab friend who really hates Arabs and lets you use racial slurs, no, it’s really cool man I use them too.

AH: As a critic I try to separate the author from the work, especially in autobiography. But it’s so difficult with The Arab of the Future. Certainly Sattouf is a complex person, and I wonder how the transition between Syria and France affected his development as a child -the New Yorker profile certainly does bring up how difficult Sattouf’s childhood was. I think a good example of the displaced author-as-character is Lucy Knisely’s recent travelogue Displacement. The Lucy of the book is clearly not the Lucy of the real world. And the same is true for The Arab of the Future, especially since the Riad of the story is lifetimes away from the Riad of the book. I think you bring up a good point about memoir in general, how the “facts” can be manipulated to achieve a desired effect. Unlike most autobiography, Sattouf certainly seems to be bending the narrative of his childhood towards a specific goal. And maybe that’s the reason that the book “succeeds” as comics, or at least has had such an overwhelming response in France. As a memoir,

The Arab of the Future

avoids all the major pitfalls of memoir comics and does so in a way that reinforces all these unspoken cultural biases, especially in a post-Charlie Hebdo France.

CM: I think that’s a good way of putting it. As I said before, it’s very technically adept, but oh man, its message is so damaging. I guess that’s the takeaway here, for me at least. Professional cartooning, reprehensible depictions of Orientalist hellscapes.

The Arab of the Future is published in English by Metropolitan Books, an imprint of Henry Holt and Company. Originally published in France by Allary Éditions.

Thanks again to CM for having this discussion with me. If you are interested in having a discussion about a recent comic you’ve read, please reach out to me at sequentialstate AT gmail DOT com.