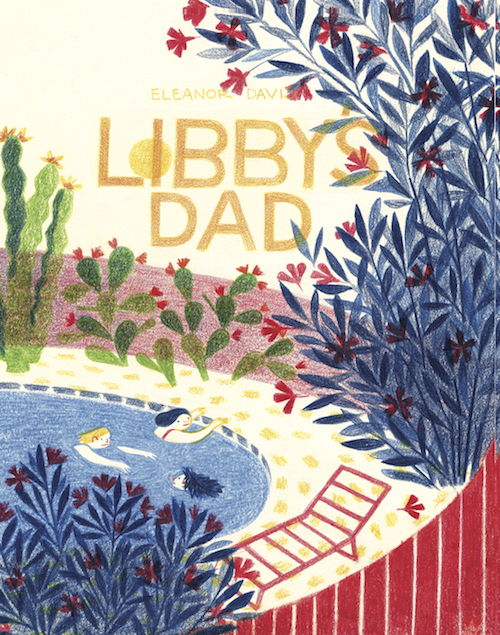

2016 was a year for Eleanor Davis comics. First it was Frontier #11: BDSM,which I reviewed in February last year. Then a big pile of pages from her cross-country bicycle trip, which are now being collected by Koyama Press. Davis’ latest, Libby’s Dad, is a 40-page full color saddle stitched comic from Retrofit. When Retrofit Comics ran the Kickstarter for their 2016 collection, Libby’s Dad was a big reason for me to take the plunge, and I’m glad I did.

Libby’s Dad is the story of a combination pool party and sleepover Libby is throwing for her friends at her dad’s new house. There are rumors circulating about Libby’s mom; how Libby’s dad threatened to shoot Libby’s mom with his gun, how her mom is crazy, and how none of it makes a lot of sense. Friends’ parents have decided to not let them come over because of Libby’s mother’s accusations against Libby’s dad. Despite the book’s seemingly simple framework, the narrative contorts the reader’s perspective and understanding.

My first observation of Libby’s Dad is how Davis perfectly articulates how children speak to one another. The conversation is casual, innocent, clique-enforcing, and sometimes cruel. There is a strong in-group/outsider power dynamic at play which feels like much of my experience as a small child. This dynamic amplifies the tension of the comic, and is a psychological fulcrum for the entire work.

Davis’ most recent works, BDSM and Libby’s Dad, both consider power dynamics in a patriarchal society. In BDSM, the overwhelming “male-ness” of the crew of the film set, the production’s intended audience, all had a specific tenor. Vic tries to stay in the in-group, in this case the male group, with varying levels of success. In Libby’s Dad, the majority of the cast is female, but it is the father figure’s actions and his abusive relationship with Libby’s mother around which all the other activity swirls. In both places Davis is making sharp observations about the state of our society and the poisonousness of its male-dominated, male-privileged features.

Libby’s Dad also focuses on the ways in which abuse affects people and how the public interacts with those people. There are no black eyes or bruises to notice in Libby’s Dad, no physical manifestations that allow us to easily cast judgement. When abuse is not physical, society’s general response is often one of indifference or distrust of the abused (when it is physical, it’s often the victim’s fault for not leaving, a key difference). Here, Libby’s mother has left, and the girls’ assumption is not that she’s been abused, but that she’s gone crazy. We see many different narrative threads at play in this comic, but clearly the abuse of Libby’s mother was enough for her to get a divorce from Libby’s father. Her face on the back of the book, the only image we see of her, is more than enough to understand the full and dark nature of what’s going on. Davis uses these striking images, one a silhouette of a gun, the other one of Libby’s mom crying over a box of Fruit by the Foot, to punctuate the comic, like a set of exclamation points at the end of a sentence. They’re gut wrenching.

Davis’s transitions are the places where the comic excels (I was going to use the word shines, but Libby’s Dad, despite its bright colors, is a very dark book). When day turns to night, the rumors surrounding Libby’s dad are tested. The things that were perfectly germane for tweens to talk about out in the sun at the pool now become terrifying and horrible. We see Libby’s friends gripped in fear that’s almost elemental. When the scene comes to its conclusion, Davis unveils the most devastating transition of the comic; the switching from that brutal, blood-curdling fear back to the previous in-group power dynamic, this time targeting Libby’s mom.

Despite the story being called Libby’s Dad, Libby herself is generally absent from the comic, at times voiceless, and I think that decision amplifies the tension of the comic and Davis’ main themes. When Libby does interact with her friends, or talks to them in a meaningful way, there’s a distance – is she indifferent, or afraid? Davis leaves this detail unclear.

Davis’ recent work has been intricately plotted and considered, and the art continues to evolve from the style of comics

published in Mome and How To Be Happy. Davis has a strong eye for shape and visual flow, and Libby’s Dad, with its panel-less pages illustrated with colored pencils or crayon, is a visual feast. The cream colored paper was a nice choice for this saddle-bound floppy, giving even Davis’ darkest blues warmth. The way each page or spread is composed shows an attention to detail that, by comparison, is missing from much of the work of Davis’ contemporaries.

Libby’s Dad is one of the best books from Retrofit’s 2016 lineup, and I highly recommend it. Find your copy before you read You & a Bike & a Road, which comes out from Koyama Press in May.

Eleanor Davis is a cartoonist and illustrator based in Athens, Georgia. You can find more work and information at http://doing-fine.com/

Retrofit Comics is a publisher of alternative comics. You can find out more about their catalog at their website.

Sequential State has a Patreon – if this reading experience was worth a dollar to you, please pledge your support. I want to build a better comics community by paying other critics to write, and hiring cartoonists to create work for the site. Your support makes those goals possible. Thanks!